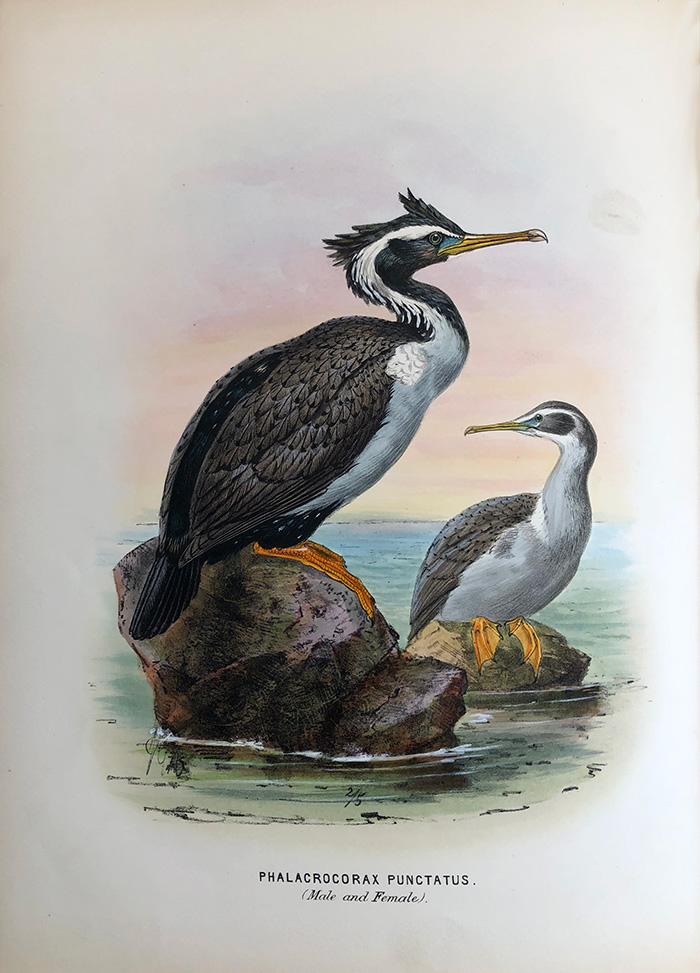

Buller, Walter Lawry, A History of the Birds of New Zealand, 1873.

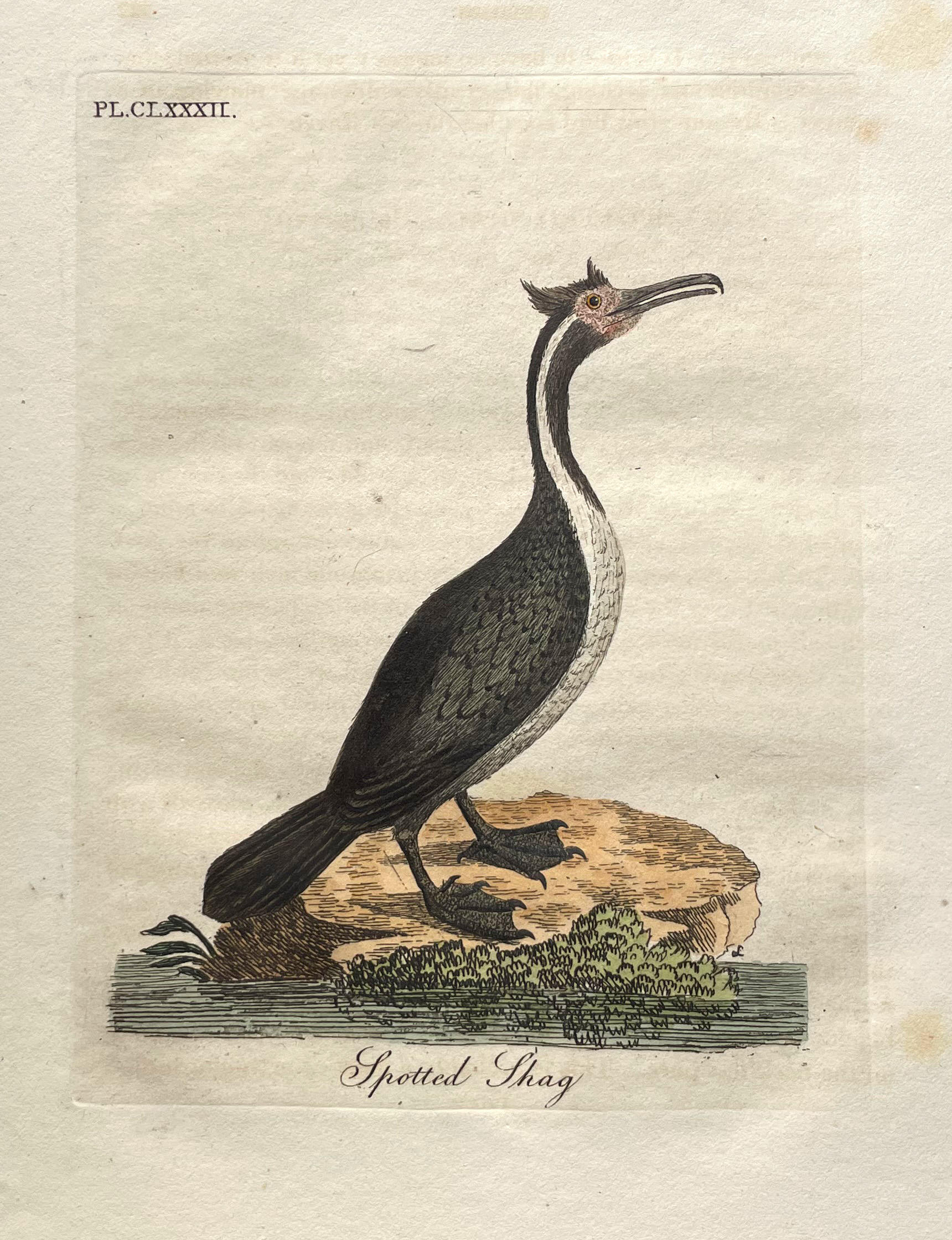

This beautiful shag was one of the species collected by Forster during Cook’s second voyage.

There are two sub species of the spotted shag, according to Heather and Robertson, punctatus, which breeds in the North Island and northern and eastern South Island, and the blue shag, steadi, which breeds around the southwestern South Island and Stewart Island. Breeding only in New Zealand, they are classified as endemic birds.

Of the world's 36 species of shag 12 are found in New Zealand and 8 of these are endemic. Members of the shag family belong to three groups based on the colour of their feet: black, yellow or pink. The spotted shag is yellow-footed. Outside New Zealand, the black-footed shags are better known as cormorants.

In the past, the spotted shag suffered persecution along with other shags and was cleared from many coastal areas where it was once common. Edgar Stead, in railing against their persecution, relates “the ghastly practice of so–called sportsmen, who used to make up launch parties, go and lie off the cliffs where these birds were nesting, and callously murder whole colonies of them, leaving the young to die of starvation in the nests”. Their numbers now, however, seem to be increasing.

The spotted shag is strictly a marine bird, frequenting rocky coasts, and not going into fresh water, excepting very occasionally as a young bird.

"For its nesting site the spotted shag selects ledges of cliffs overhanging the sea. It is on this account that Banks Peninsular is such a favoured resort, for there the volcanic cliffs offer many ledges that are ideal for them. The young are fed by both parents while in the nest, in the ordinary shag manner. It is quite usual to find red–billed gulls hanging around a spotted shag colony — in fact they often establish their own nesting colony nearby. When the young shags have been fed and the parents have left for the sea to get more food, one of the gulls, which have been watching the whole performance, immediately flies to the nest and, standing on the edge of it, swears at the young shags (the gulls whole manner and tone of voice conveys just this impression), who forthwith disgorge some of their food, which the gull promptly eats. The gulls continue to do this up to the time when the young shags are getting their feathers, by which time the shag is a good deal larger than its persecutor."

In the first quarter of the year when the young are all able to fly, according to Stead, whole parties of them and their parents go on long journeys up or down the coast. “In July or August, if the outlet to Lake Ellesmere is open, numbers gather in the sea outside to feed, diving among the breakers and coming close inshore in pursuit of the silveries which are running into the lake”.

“At this time, many of the birds have attained their full breeding plumage, and it always gives me a sense of incongruity to see them so wonderfully attired yet going about their daily work; for there is no doubt that spotted shags, when they do attire themselves in the vestaments of courtship, make a job of it — there are no half measures. They grow two forward–curving crests of long soft dark feathers, one on the front of the head, the other on the nape. The front of the neck becomes black, and this is separated from the dark back of the neck by a broad white stripe which runs from the bill, above the eye, right down to the shoulders, the whole of the upper part of the neck being thickly studded with long white filoplumes. The breast and abdomen are pale blue–grey, with a curious sheen, suggestive of having been touch with aluminium paint. They don their lustrous dark blue trousers, covering their flanks, lower abdomen and rump, and these too are flecked with filoplumes. The bare skin of the face becomes brilliantly coloured: a ring of greenish blue encircles the eye, and merges into the rich royal blue of the face and throat. The feathers of the nape, scapulars and upper wing–coverts are brownish grey, each having a conspicuous black spot on its tip. In these regions too there are a few white filoplumes, and extra long one issuing from the elbow joint. Both cocks and hens acquire this gay dress, and in equal degree. And so the birds go courting.

“Alas, for romance! It must be reported that all this finery outlasts mating by a week or so. Even before the nest is begun the dainty white filoplumes have commenced to fall out, and by the time the eggs are laid, few, if any, of these transient ornaments remain. The two crests quickly follow them and ere the first chick chips the shell the fine sooty black of the under neck is beginning to fade, the white stripe is dotted with black, and the birds are going back to their workaday dress”.

The food of the spotted shag consists mainly of small fish and crustaceans and, according to Stead, when there is a migration of whale-feed, britt,or krill along the coast, the birds subsist almost entirely on it. They usually travel to and from their feeding grounds in flocks, flying with a quick beat of the wings, just above the surface of the water.

According to Rob Schuckard, cormorants and shags belong to “flapping species”. Due to their high wing loading (high weight in relation to wing surface) in combination with a lack of sufficient muscle power to fly at the most energy efficient air speed, the energy use to reach feeding areas is among the highest of all seabirds. They must “flap” at their maximum capability. To compensate for this disadvantage, they fly near the surface of the water to save energy through “ground effect”. The air below the wings is compressed and it cushions the body. This is equivalent of lessening the weight of the bird and is most apparent just after take-off when they still do not have their maximum speed.

In response to a question about why shags disgorge stones on the beach, Rob Shuckard offered the following hypothesis: — Spotted shags are pelagic feeders. Though not a lot of information is available about the food, they are often seen together with big flocks of fluttering shearwaters most likely targeting fish like pilchard and anchovy. Pilchards are reported as visible schools in Tasman Bay and Marlborough Sounds from October to March. This is the time of spawning and enormous clouds of fish cream of the surface layer of the sea for diatoms. During the rest of the years they are deeper. When pilchard are near the surface, it may well be that shags need extra weight to overcome positive buoyancy. For example buoyancy of reed cormorant, Phalacrocorax africanus from Africa declines with depth and becomes neutral at 5 meters. If a similar model of buoyancy compensation would apply to spotted shag, the use of pebbles may help them to feed in the top surface of the water. It would therefore be rather interesting to see if the use of pebbles is seasonal (October to March) and not necessary when food is hiding deeper(>5m) in the water.

| Taxonomy | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Phalacrocoracidae |

| Genera: | Stictocarbo |

| Species: | punctatus |

| Sub Species: | puctatatus, steadi |

Endemic bird

70 cm., 1200 g. Slender grey shag with yellow feet, slender brown bill. Adult has small black spots on back and wings, rump, tail and thighs black, underparts grey. A broad white stripe from above eye down sides of neck and conspicuous double crest are the most telling characteristics. Juveniles lack the crest. See text for breeding plumage.

Breed Hauraki Gulf, Somes Island in Wellington Harbour, Marlborough Sounds, Kaikora Coast to Banks Peninsular, North Otago to the Catlins, West Coast.

Spotted Shags in breeding plumage. — Kathleen Shepherd

Shag stones on Sumpter Wharf, Oamaru. (March2005) — Nick Barber

Spotted Shags in breeding plumage, Kathleen Shepherd.

Shag stones on Sumpter Wharf, Omamaru, Nick Barber

Buller, Walter Lawry, A History of the Birds of New Zealand, 1st ed. , 1873.

Latham, John, The General History of Birds, 1821–28.</p>

Stead, Edgar F., The Life Histories of NZ Birds, 1932.

Oliver, W.R.B., New Zealand Birds, 1955.

Heather, Barrie, & Robertson, Hugh, Field Guide to the Birds of NZ, 2000.

Rob Shuckard, OSNZ.

Parekareka, spotted shag, from Latham's The General History of Birds, 1821–28.

Sunday, 29 October, 2023; ver2023v1